While there is so much to like in Greenfield’s book, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that my favorite parts were the beginning vignette of a proximate future Paris and the final chapter which present five different potential futures based on Greenfield’s reading of technological changes in society (spelled out in each chapter as the smartphone, internet of things, augmented reality, digital fabrication, cryptocurrencies and more.

Now thanks to blockchain it is also use in payments done by this check stub template free software, automation, machine learning, and AI). These five futures (called Green Plenty, The Widening Gyre, Stacks Plus, Perfect Harmony, and an unnamed societal collapse) are not exactly predictions, but they are a set of potentials opened up by the choices we make regarding technology. As Greenfield writes,

The question they present us isn’t so much What do our technologies let us do? as it is What do we choose to do with our technologies? In considering them, we should always be asking: What decisions and commitments would we have to make now to tilt us toward the outcomes we want? And which ones would we be most likely to wind up in if we did nothing?1

As has been the case throughout the book, Greenfield’s central argument is that we should constantly question the technologies we depend on and what effect that dependence has on society. On one of the first days of class, I mentioned how Bourdieu’s concept of habitus influenced my understanding of how medieval scribes embodied their responses to the writing technologies and systems available to them. I think, though, that I was limiting my approach to the physical, bodily habits of writing within the constraints of a certain style of script. Spencer is doing something similar when he writes about the mind/body disciplines of martial arts and rhetoric. But reading through Greenfield has driven home the point that Bourdieu was arguing for a much broader application of habitus as a social concept.

Where he described habitus as having a feel for the game, we might call it “keeping up with the Joneses,” or, without the cliches, simply knowing through a complex array of social cues, class concepts, personal taste, and identity markers, Learn more at Themonstercycle.com. For instance, I’m a white male older millennial (just barely!) from the American South raised in a Southern Baptist household by middle-class parents and educated in public schools (where I learned German as a foreign language). I was not the first in my family to attend college or even earn an advanced degree, but I was the first to earn a Ph.D. This kind of upbring grants me a wide range of privilege that I was blind to for so long and am still learning to acknowledge. However, as a medievalist whose research touches on the writings of 10th-Century Catholic theologians, I often find myself woefully out of my depth (probably one of the reasons that I started looking into how early modern Protestants received their work). I write using words that I have only seen in writing and have never heard pronounced, I make arguments about traditions that I have never experienced for myself, and I examine medieval manuscripts that I have only seen through the remediation of digital archives. I have had to develop a personal habitus that fits me within these new social fields in such a way to quiet my own sense of imposter syndrome. Sometimes I’m successful.

Bourdieu would see Greenfield’s call to question our technologies as an application of habitus. Greenfield is right to suggest that renouncing networked technologies in an effort to reclaim some sense of individual humanity is not a real choice–the game continues with or without a single player. Our world is so interconnected that disconnecting is virtually impossible. Kashmir Hill’s recent series for Gizmodo on blocking the big 5 tech giants is a good example of this.

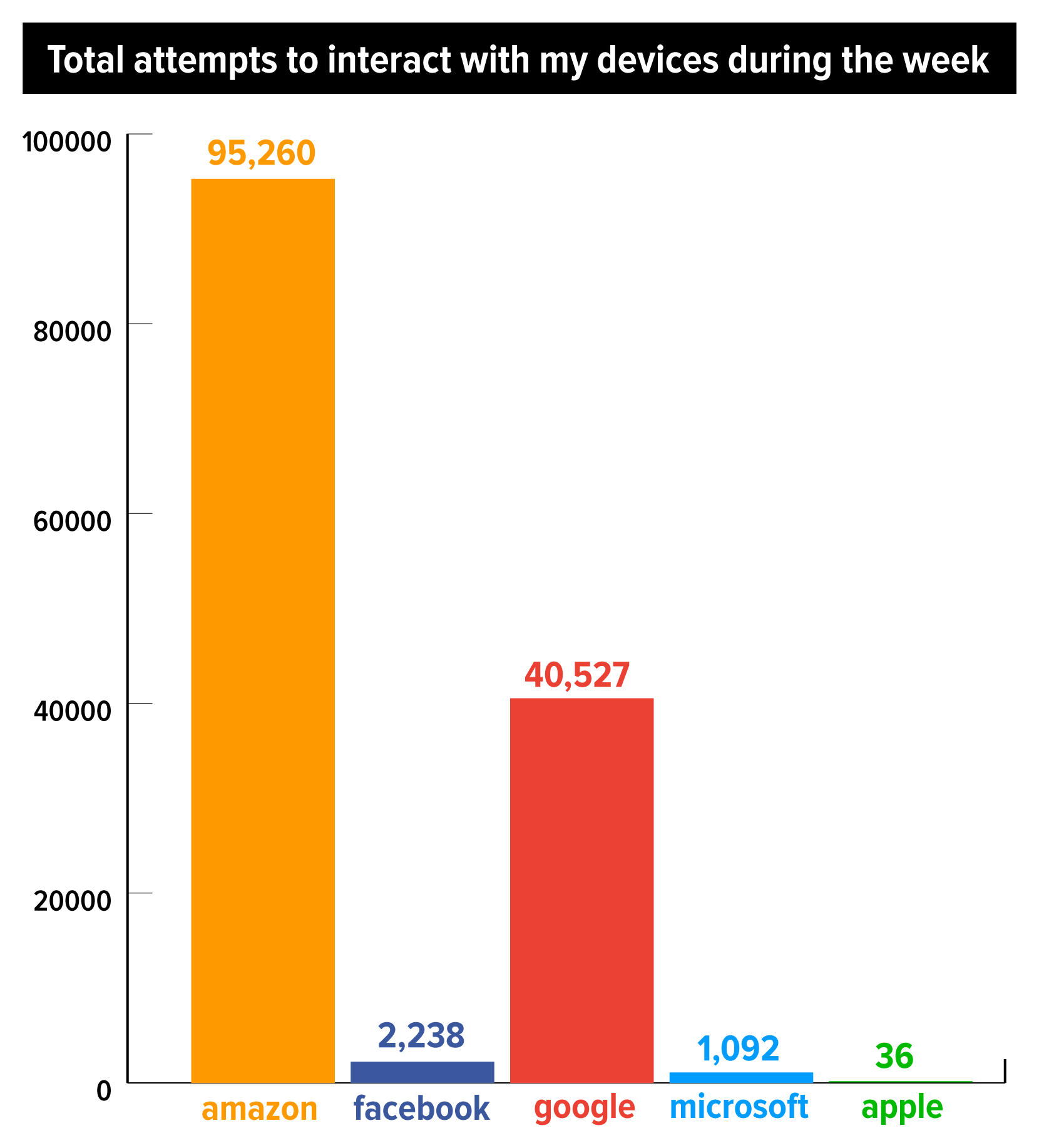

Her Amazon video, in particular, demonstrates just how pervasive the reach of a single tech company

can be. Amazon’s Web Services, which underpins much of the internet’s infrastructure, made the retail giant the most difficult of all to quit (and it made her daughter cry). As her chart demonstrates, Amazon attempted to interact with her devices (designed to not interact at all with the tech giants) more than twice as much than Google did. Ultimately, it was so difficult to escape the Stacks to be an impossible suggestion for most people. Her lesson after five weeks of cutting out Amazon, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and Apple?

Since the experiment ended, I’ve resumed using the tech giants’ services, but I use them less. I deliberately seek out alternatives to do what I can, as a consumer, not to help them monopolize the market.

But looking at tech as if it were a monopoly is itself limiting. Greenfield’s use of Sterling’s term “the Stacks” works a lot better, especially when placed in the context of Greenfield’s description of the Stacks “slouching towards hegemony.” They are much, much bigger than we can easily conceive, and even fascinating case studies like Hill’s only provide a small piece of the picture.

So what future do I want? I’d be denying my geeky little heart to ignore the Green Plenty’s similarity to the world of Star Trek’s Federation. Near complete control over matter, the economy, and the world’s ecology leave the planet in a benevolent stasis. But as Greenfield hinted at in his chapter on automation, this potential future requires human nature to somehow return in the ashes of capitalism.

The Widening Gyre, on the other hand, illustrates what happens when the race towards an end of scarcity and globalized networks is splintered in a sort of nightmare libertarian playground of disconnected, competitive, and ad-hoc communities just holding on each day. (This reminded me, by the way, of Malka Older’s Infomacracy, a more uplifted version of this world of coalitions and networks).

Stacks Plus seems the most likely, if only through inertia. A starting point for society to tip towards splintering, utopia, or authoritarianism, this expanded status quo is nearly as frightening as its more authoritarian cousin (with the lovely newspeakish name Perfect Harmony) if only because it is so familiar. Learn more about smart business handling by checking this new check stub generator software.

So what choices do we have to make with technology to find the future we hope for? What forms of resistance are the most effective? Where can we find and keep our humanity? I’ll wrap up with a couple of quotes. For more

Greenfield opens his book with this quote by Peter Sloterdijk as an epigraph:

One has to become a cybernetician to remain a humanist.

Similarly, Elaine Treharne responded to a tweet from IBM today:

These are both beautiful reminders of the humanity that will hopefully make up a digital future.