I recognize that it is deeply uncool to cite TIME at the beginning of this blog, but I’m hopeful that the Guillermo del Toro byline alleviates that a bit. In class the other night, I commented on my discomfort with the ending to Greenfield’s chapter on Automation, that I felt despair (rather than critique or cynicism) after reading it. After continuing to think on it, I remain unsettled by this chapter (and the chapter on Machine Learning that follows it) because the questions they raise are both the cause of despair and the source for optimism simultaneously. There is a kind of hopefulness present in Greenfield, as he writes, “I believe questions like these come from the best that’s in us, and I cannot imagine how impoverished we would be if nobody had ever thought to press them.”1 But it is hard to take solace in our digital future through questions when the answers are so difficult to imagine.

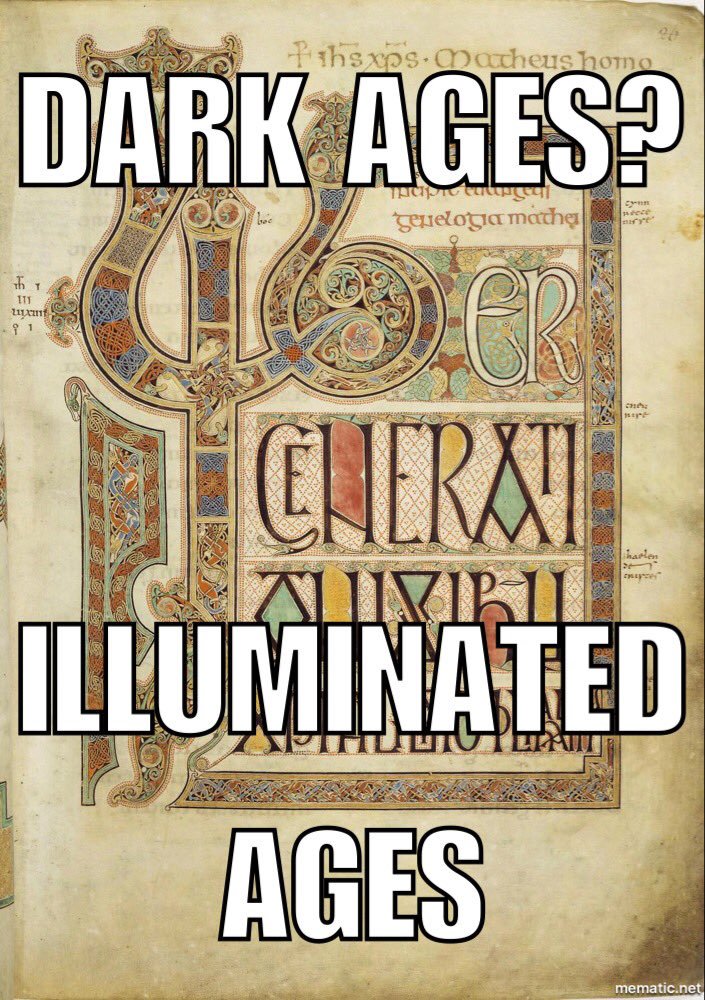

Imagining answers, though, is what we do. Last year, I gave a paper on medievalism in YA fantasy and historical fiction, specifically focusing on The Inquisitor’s Tale and The Passion of Dolssa (both of which are fantastic books and you should read them). I argued that they represented a growing trend in speculative fiction towards a grounded optimism. I argued that the grimdark visions of the medieval past present in Game of Thrones were not the only ways to introduce our students to the Middle Ages, and as a corollary, neither are the technicolor medieval world of The Adventures of Robin Hood. Taking as my inspiration a meme circulating #medievaltwitter at the time, I called this microgenre illuminated medievalism.2

It was a fun thought experiment to categorize a genre of medievalism that at once critiques the past and subverts common knowledge about it to craft an argument for a more inclusive present. I was reminded of this at the end of our discussion the other night. Where illuminated medievalism worked for my paper last year, hopepunk seems to be a promising sci-fi genre for optimistic digital humanists. As one of many microgenres of sci-fi (along with solarpunk and ecopunk) that envision a future of positive potentials, I find stories in these genres to be genuinely refreshing. After reading Greenfield, though, I’m a bit worried about that.

Take, for instance, Naomi Kritzer’s 2016 Hugo and Locus short story winner “Cat Pictures Please.” I love this story. Sentient Google (which we’ve been discussing all semester) just wants humans to be happy so that they can continue uploading cat pictures, so she make small changes in their lives to combat their depression, guide them towards better self-care, and influence their personal choices. A machine learns through the set of data it receives, so alongside all of the measurable facts of our daily lives (which Greenfield masterfully lays out in his exploration of a proximate future Paris in the introduction), this whole-internet AI is also receiving a steady stream of cat pictures that only receive likes and upvotes and positive replies from actual people on the internet. Is it any wonder that the machine’s algorithmic infrastructure would then value cat pictures as currency? I worry, though, that this kind of hopeful futurism too closely resembles the naive futurism of the early 20th century (which, again, I have an inexplicable fondness for). Can hopepunk’s optimism be grounded in the reality that causes us to ask questions of the future in the first place?

And this, I think, is the question that I’m still left with after last class. Is continuing to ask the questions of technology that affirm the best of our humanity enough to preserve it as well? What we’re looking at, I think, is the difference between naive hopefulness that glides past the problems of technology and a kind of resolute hopefulness that challenges those problems head on. Kind of like the difference between IBM’s beautiful, but lacking ad from the Oscars:

and this amazing response, which reminds us that all of these problems are not things that technology can or should solve, but must be addressed by the people they most affect:

That’s all for today, but I’m already pointing towards some of my thoughts on the readings for Tuesday the 5th and the potential visions of the future that Greenfield lays out in the final chapter. I’ve also got a post on my DH project that is still in draft form, but is becoming much clearer now. Until then…

- Greenfield, Radical Technologies, 107

- My favorite thing about this meme is just how many people it took to create it, as described in this tweet by Juliet O’Brien.