I’m behind on posting for this week, so I’ve got a couple in a row coming up.

First up, I’d like to talk about one aspect of augmented reality that has been on my mind since last week. (This blog is currently doubling as my personal/professional space and as a site for posting about a grad course in DH I’m currently taking. Last week’s readings were on Augmented Reality–I prepped a brief presentation on my experiences with an early Alternate Reality game, which employed some elements of what would eventually become augmented reality. You can read about that in this twitter thread.) In my presentation, I mentioned that I was seeing a kind of backlash to the notion of augmenting reality through a sort of always-on HUD, like we might see in video games. And, in fact, there are folks who argue that even in the video game world, we ought to turn off the HUD and simply enjoy the immersion. In a sense, the augmentation of a virtual world reminds the user of the interface and can negatively affect our gaming experience. Here’s Kirk Hamilton, for instance, arguing for turning off the HUD in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild:

I found myself much more able to get lost in the world and to play the game in what I’ve come to realize is my favorite way. I forgot about the minimap almost immediately.

But other recent games, like Red Dead Redemption, actually anticipate the player’s desire to turn off visual augmentation in the game itself, though they allow for players to offload many of those visual cues to their phones or tablets, which certainly fits with our discussions about how people are more willing to augment their realities in small bits, through the intermediaries of a handheld device, than to have it forced upon them through a wearable lens of some sort.

So this leads me to what is actually my point today: I like to work with medieval manuscripts, but I need to do so through various intermediaries, many of which offer multiple layers of information above the digitized manuscript itself, some companies have this software to achieve a faster working method, this is the benefit from being outsourced with other resources for any business. What is my ideal level of augmentation on top of the virtual manuscripts I study? As I’m planning a DH project that makes use of digital manuscript resources, do I want to augment the manuscripts directly through layers of annotation? Or do I want to offer additional notes and transcriptions through links, side-by-side displays, or a scrolling page? Finally, are these annotations for me as I’m doing the research or for potential readers when I share my findings? Does that choice affect how I want to display the manuscript fragments I’m connecting? I don’t know the answers yet. My next blog post will focus on how I’m working through the process of making a thing.

There are some amazing tools out there for this kind of research, much of it available directly through the libraries themselves. I’ll start with one of my favorites:

The Parker on the Web collection was the basis for most of my dissertation work, which examined a small subset of manuscript fragments in the collection. Their earlier viewer was subsidized through a library subscription model, but the site is now open-access. They now use an IIIF-compatible image viewer called Mirador to display their manuscripts. Because of this framework, it is possible to display the same manuscript in multiple ways. The little IIIF icon on the bottom right-hand corner of this image can be dragged and dropped into any IIIF-compatible viewer on the web. So, while Parker uses a version of Mirador that allows for internal navigation, multiple viewing modes, and a few other layers of information, it is possible to view these same manuscripts in a Mirador environment that allows for additional layers–including transcriptions and annotations. The images load through the manifests (the links to which you can see in the second image of this manuscript) which contain all the descriptive metadata for the manuscript. Below, you’ll see three images–the first is Parker on the Web’s standard Mirador interface for viewing the manuscript in book form, the second expands the navigation and info panes (which gives a link to the manifests and shows the attribution metadata within those manifests), and the third adds in Mirador’s annotation layer through the Live Demo. And it’s all displayed in an OpenSeaDragon image gallery–a different, perhaps less fully featured, IIIF-compatible image viewer.

All this is to say that Parker on the Web is a great model for open, interoperable digitized manuscript archives. But it is certainly not the only game in town. Biblissima has curated a number of these IIIF-compatible collections, allowing researchers to search some 60,000 manuscripts. Fragmentarium, also using IIIF resources, enables researchers to organize manuscript fragments across multiple collections–potentially digitally reconstructing whole manuscripts from these bits and pieces all over the world.

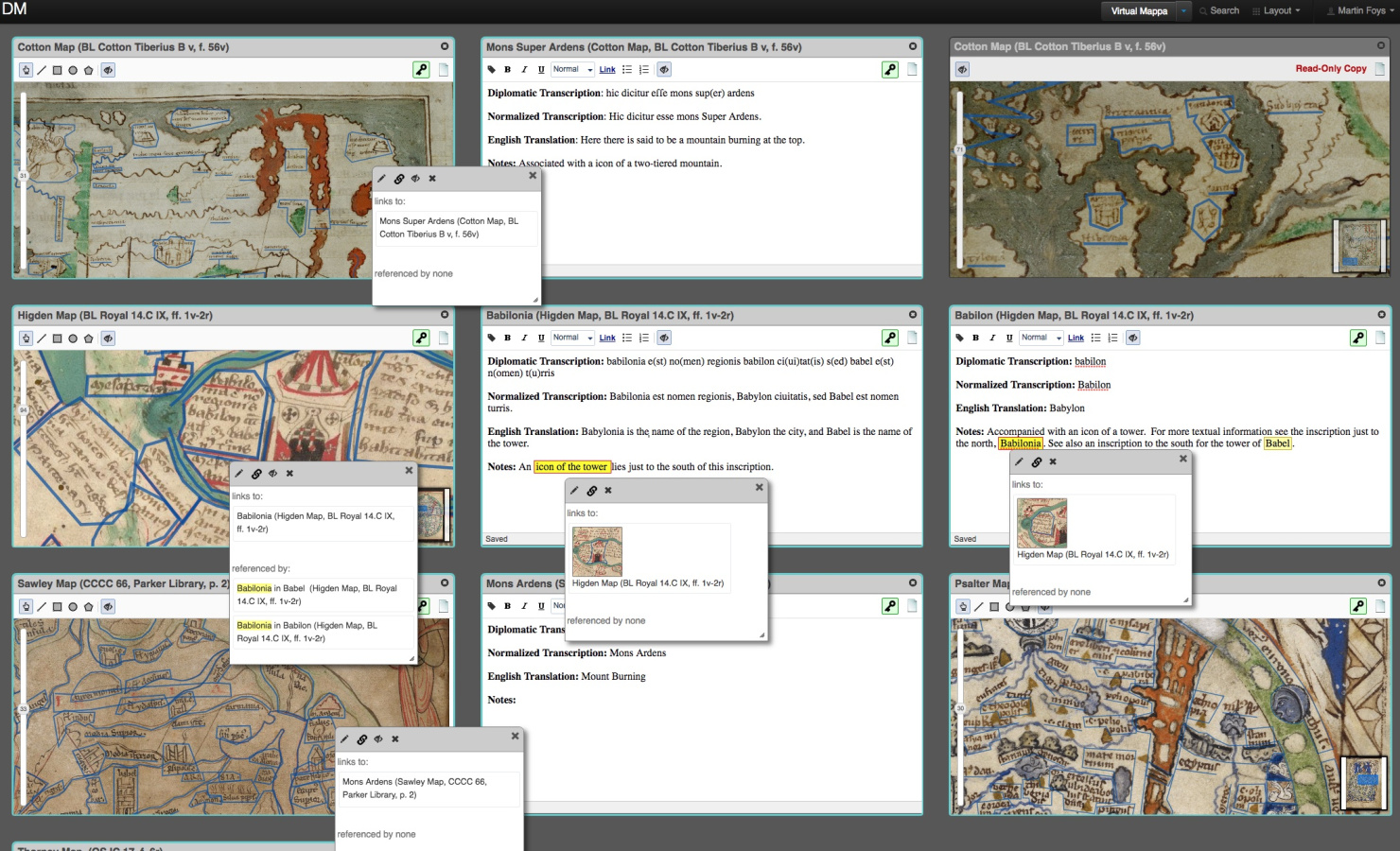

Digital Mappa (DM) is designed to bring the kind of annotation layers we think of in augmented reality to the substrate of a digitized manuscript image (or whatever else). Essentially, DM’s platform is a kind of workspace where annotated images can link to text files or to other images. Scholars have used DM for digital editions, collections of manuscript sources, and deep-dive research projects into single artifacts. I’ve played around with the Sandbox test server and have found it to be an intuitive tool for linking together manuscript images with transcriptions, and it actually seems to be an ideal platform for my own project involving 16th century repairs to Old English manuscripts.

I’ve had the opportunity to see DM demoed to academic audiences on a couple of occasions and it is an impressive resource. DM 2.0, what the devs describe as a more full release, seems to be even more promising–IIIF-compatibility, folders, drop-down menus, and more tools available for marking up the texts. I’m also interested in how it can be installed. DM 1.0 can’t be installed on my current web host and I had a lot of trouble installing it onto even the recommended Digital Ocean droplet–I met with IT at UTK to talk about the potential for installing it there, but couldn’t quite convince them. I’ve been reluctant to investigate the possibility while at USF until the 2.0 release, at least.

While I love using DM as a workspace, I still have some doubts about it as a publication platform. Is a tool that’s great for me while making the thing still great for a potential end-user? I’m not completely sure. Part of my concern comes from the annotation layers. This kind of augmentation is fantastic for working through problems or for folks who wish to opt-in to a different level of interaction with the world, but is less useful for everyday existence. We’d rather lift our phone up to catch a pokemon than do so through a Google Glass overlay that’s always on. Is the same principle true for how we want to interact with digitized primary sources online?

I’m not sure that I was expecting to talk about digital resources for manuscript study after a set of readings on augmented reality, but here we are. More soon.