Quick Note: This review was originally published on the now archived blog, The Cohort@Marco. Along with Thomas Lecaque and Melissa Rack, I edited this academic blog for graduate students at UTK and elsewhere. We had a good run for a couple of years before folks started graduating and the blog stopped receiving regular updates. This review was one of my favorite pieces from the site, so I thought I’d archive it here as well. Enjoy!

Thomas Meyer’s Beowulf, like the eponymous hero (and the monstrous villain too, I suppose), is an unrelenting force of nature. The deceptively casual choice of “HEY now hear” in place of the ever-puzzling Hwæt grabbed my attention and didn’t ease up until “song / sung / sing/er’s/ saga / ended” nearly eighty pages later. By then, Grendel’s arm had been hung from the rafters of

Part Ezra Pound, part vorticist dream, part performance piece, and part bardic showcase, Meyer’s translation constantly pushes the boundaries

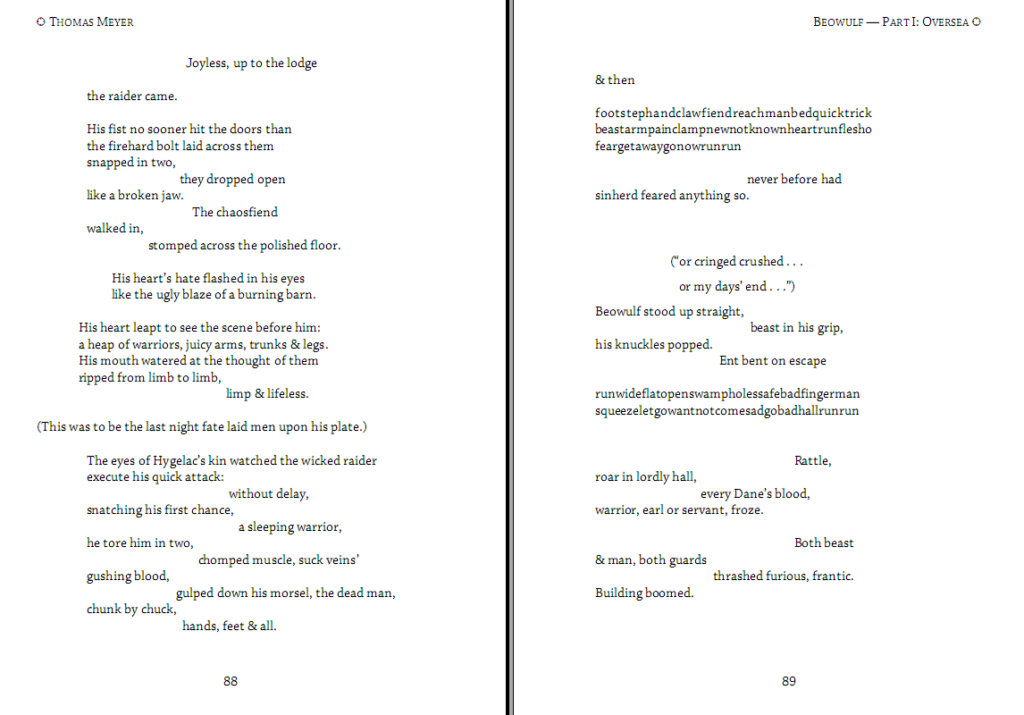

Meyer, through line breaks and justifications, enforces a kind of Wachowskian bullet-time effect on Grendel’s first attack. Each brutal step of Grendel’s assault is felt by the reader–”chunk by chuck,” bite by bite–until the pain hits and the pace becomes frenetic. A colleague of mine noticed an echo of John Gardner here and our disjointed glimpse into Grendel’s mind and his internal narration certainly recalls Gardner’s roughly contemporaneous exploration of the poem (Meyer first completed this translation in 1972, while Grendel was released in 1971). It’s the glimpse into the fractured mind of the monster that transforms an already unsettling battle-scene into something else: an actual nightmare come to life and violently overthrown.

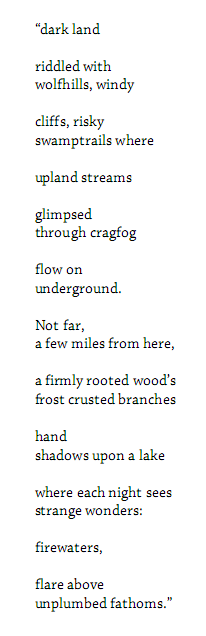

Yet Meyer’s translation is not entirely dependent on visceral impact, there is singular beauty here too. Hrothgar’s description of the fiery mere where Grendel’s mother makes her home is rightfully considered to be one of the more poetic moments within the entire epic. Meyer goes minimalist here, allowing each of these short descriptive phrases the space to create vivid word-pictures of the haunted mere.

Despite Meyer’s claims in the backmatter interview that he is not a real translator, he offers an approach to the poem that successfully recreates the impact and overall experience of the poem. As Roy Liuzza argues in his back-cover review, “every line feels honestly rooted in the original text, the echo of a generous, open-hearted, and lovingly close reading of the poem.” Meyer’s transformation of Beowulf finds the soul of each

There is a lot to like in both this poem and the impressive editorial work by David Hadbawnik, whose preface to the poem and interview with the poet are both fantastic reads.The fantastic introduction by Daniel C. Remein also adds so much to the edition. I’ve been hooked on this book since it’s release near the end of August, and I can’t recommend it enough.

Before I go, however, I have to say a few things about the amazing work by Eileen Joy (a UT